Animal cloning has emerged as a significant point of contention within both scientific circles and ethical discourse. As we examine the juxtaposition of science and ethics in the realm of animal cloning, we must delve deeper into our understanding of sentience, the essence of life, and the implications of meddling with nature’s intrinsic design. At its core, the practice raises compelling questions about what it means to be an ethical steward of the animal kingdom, inherently calling into question not only the scientific processes involved but also the ethical ramifications that follow in their wake.

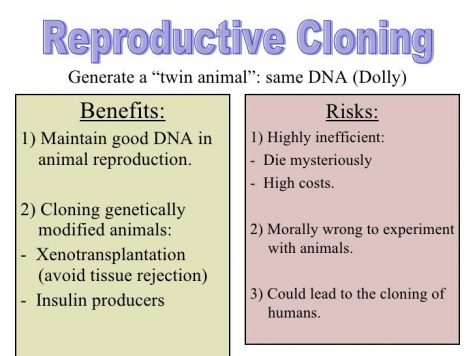

The process of cloning animals—replicating an organism’s genetic material to produce a genetically identical copy—is often perceived as a remarkable advancement in molecular biology. Proponents herald its potential for agricultural enhancement, conservation of endangered species, and even the possibility of eradicating genetic diseases. However, beneath the veneer of scientific progress lies a veritable moral labyrinth filled with potential pitfalls, reminiscent of Pandora’s box. Opening such a box may reveal unforeseen consequences that could spiral beyond the purview of human control.

It is crucial to differentiate between the sheer capability of cloning technology and the ethical implications of its application. The mechanism itself involves intricate methods such as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), wherein the nucleus of a somatic cell is implanted into an egg cell devoid of its nucleus. This procedure births entities like Dolly the sheep, the first mammal to be successfully cloned from an adult somatic cell. Yet, Dolly’s poignant tale is marred by issues of animal welfare. She lived only a fraction of her potential lifespan, mired in ailments that ranged from arthritis to lung disease, raising questions about the suffering inflicted upon these sentient beings in the name of science.

One cannot dismiss the notion that cloning often compromises the well-being of the animal subjects involved. The cloning process is notoriously fraught with inefficiencies. For every successful clone, there are a multitude of failures: miscarriages, abnormal growths, and perinatal deaths are tragically common. In the sterile, clinical environment of laboratories, these beings encounter a series of existential crises that they never asked for—a poignant metaphor for a world that often prioritizes progress over sentience.

When viewed through the lens of ethics, the concept of animal cloning encounters formidable opposition. Ethical frameworks such as utilitarianism, which promotes actions that maximize happiness, challenge the viability of cloning as a moral endeavor. The suffering of numerous failed clones versus the potential benefits to humanity creates a potential ethical quagmire. Is it justifiable to sacrifice these lives, potentially fraught with pain and suffering, for the perceived benefits of a select few? It beckons a fundamental inquiry into the nature of sentience: do we, as rational beings, possess the autonomy to dictate the lives of those who cannot voice their consent?

Furthermore, the ambiguity surrounding the concept of individual identity complicates the ethical discourse surrounding cloning. Each cloned animal is genetically identical to its predecessor yet lacks the experiential, memorable, and emotional tapestry that defines individuality. This deviation from unique life experiences leads to a contentious debate about whether a cloned animal is merely a reflection of its progenitor or an autonomous entity entitled to its own existence. The emulation of life strips away the respect afforded to personal identity, rendering these creatures as mere vessels of genetics rather than unique beings deserving of dignity.

Moreover, the environmental implications of cloning introduce additional ethical dilemmas. The pursuit of cloning to achieve agricultural efficiency may inadvertently lead to biodiversity loss. By favoring specific genetic traits, we could unwittingly diminish the gene pool vital for resilience against disease and environmental changes. In many ways, cloning mirrors the dilemma of monoculture, where the pursuit of a singular crop variety jeopardizes the broader ecosystem. The consequences ripple outward, creating a precarious balance in the intricate web of life, which can only be sustained through diversity.

Yet, some argue that animal cloning can play an instrumental role in conservation efforts. The possibility of resurrecting species on the brink of extinction, or of rescuing those already lost, presents a tantalizing allure. However, the ethical dichotomy remains: can we restore and revive, when the same technology violates the sanctity of existing forms of life? The question hangs like the unresolved tension within a symphony, waiting for the conductor to decide on a resolution.

Ultimately, the interdisciplinary dialogue between science and ethics necessitates a more nuanced understanding. Collaboration amongst scientists, ethicists, and animal advocates is essential to unveil the complexity of cloning ethics. As the scientific community forges ahead, the imperative remains to tread lightly, to honor the sentience of animals, and to remain vigilant stewards of the planet’s biodiversity.

In conclusion, while animal cloning may appear as an emblem of scientific prowess, it invites us to consider the profound ethical ramifications that accompany such endeavors. This technological prowess can be likened to a double-edged sword; it has the potential to either uplift the natural order or disturb the moral compass that guides our interactions with the animal kingdom. Engaging in this discourse is not merely an academic exercise but a moral imperative to ensure that our pursuit of progress does not come at the expense of compassion. After all, in the intricate tapestry of existence, every thread, no matter how small, holds significance. We must ask ourselves: How should we weave these threads together? The answers are as varied and intricate as the lives of the beings we seek to preserve.