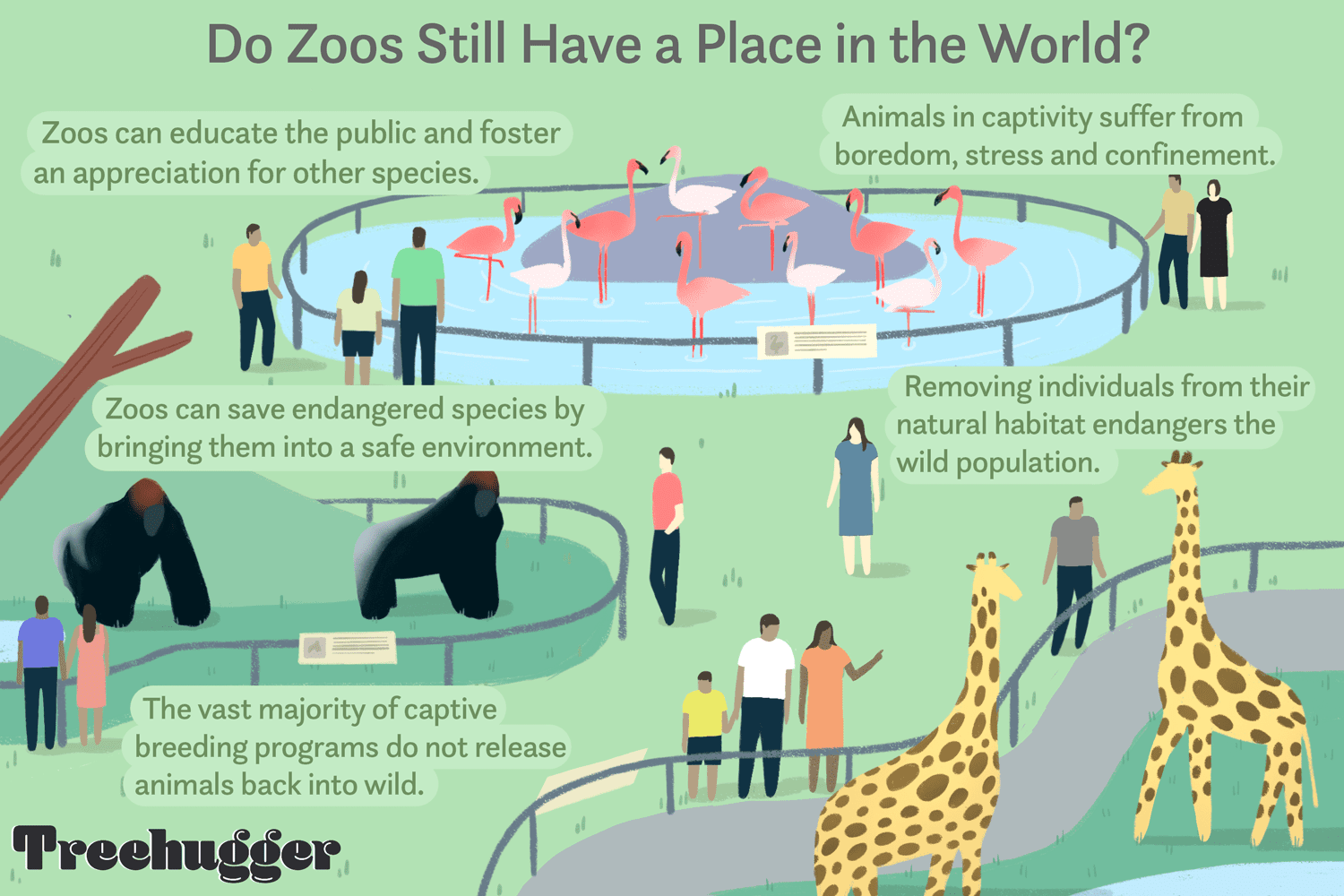

In contemporary society, the ethical landscape surrounding zoos has never been more contentious. Conversations about animal welfare, conservation, and public entertainment conjure a plethora of perspectives that warrant scrutiny. Are zoos, in their current iteration, benevolent guardians of biodiversity, or do they perpetuate systems of cruelty that harm the very creatures they claim to protect?

Historically, zoos operated under a philosophy of display, emphasizing entertainment rather than education or conservation. Animals were often relegated to cages in enclosures that poorly mirrored their natural habitats. Consequently, they experienced substantial stress, leading to a myriad of psychological issues. The archaic practices of capturing wild animals and housing them in artificial settings raise pressing ethical questions: Is this truly a sanctuary for species on the brink of extinction or merely a modern pantomime of nature?

In efforts to reform these institutions, an array of zoos have transformed into conservation-focused entities. Many have integrated breeding programs, educational outreach, and habitat restoration endeavors, claiming to address the plight of endangered species. Advocates argue that without such facilities, many species would face assured extinction. Yet, a dichotomy emerges between those species considered “charismatic megafauna”—like elephants and tigers—and less aesthetically pleasing species that often languish in obscurity. This preferential treatment raises questions about the intrinsic value of animals that fail to captivate public interest.

Compounding these issues is the concept of animal agency. While it is widely accepted that many creatures possess varying degrees of cognitive abilities, the loss of autonomy in captivity remains a critical concern. Wild animals can travel vast distances, form complex social structures, and engage in instinctual behaviors that arc toward instinctual freedom. Confinement—regardless of its amenities—restricts these essential behaviors. In assessing the ethical ramifications of maintaining animal life behind bars, one must grapple with these constraints imposed by artificial environments.

The ethical debate extends well into the realms of academic discourse as wildlife conservationists and animal rights activists clash over methodologies and ideologies. One maintains that zoos provide a necessary refuge for species threatened by habitat destruction, poaching, and climate change. The other posits that even in the name of conservation, captivity is an egregious violation of animal rights. Innovations in technology, such as wildlife tracking and genetic research, raise an intriguing question: Can humans play a role in animal preservation without breaching ethical boundaries? Is it possible to foster a nurturing environment that supports wildlife from the sidelines rather than from within enclosures?

Advocacy for alternatives to zoos is gaining momentum, with sanctuaries and rescue centers emerging as viable contenders. Sanctuaries prioritize rehabilitation over exhibition, offering a more idyllic existence for animals previously subjected to cruelty. Such institutions urge a paradigm shift: instead of exhibiting living trophies, we should offer sanctuary. These sanctuaries provide the opportunity for animals to experience more autonomy, interacting with their species in environments that better reflect their natural habitats.

Yet, the movement toward sanctuary models is riddled with challenges. Funding is often precarious, and the ability to sustain these facilities without resorting to tourist attraction is a prevailing concern. Moreover, the public’s appetite for witnessing exotic animals remains insatiable. Initiating profound educational programs about wildlife conservation without glorifying captivity remains a delicate balancing act. How can we stoke curiosity about wildlife while fostering respect for their autonomy?

One cannot overlook the psychological impacts of captivity on animals. Studies have documented abnormal behaviors—such as pacing, self-mutilation, and stereotypies—among captive animals. Such manifestations of distress highlight a compelling argument that, despite improved enclosures with enriched environments, many of the animals remain deeply affected by their unnatural lifestyles. It is imperative to consider whether efforts for improvement genuinely ameliorate lived experiences or merely serve to pacify public scrutiny.

On a broader scale, there exists a social and cultural imperative to revisit our relationship with the animal kingdom. We must confront uncomfortable truths about humanity’s proclivity to dominate and exploit. The sentiments evoked by observing animals in captivity can engender a false sense of familiarity and desensitization to their plight. The ethical dilemma lies in whether the immediate gratification of witnessing the splendor of a Bengal tiger is tempered by a deeper understanding of its needs, habitats, and rights as a sentient being.

As we navigate the complex narrative surrounding zoos and animal captivity, it is crucial to foster conversations that challenge our ethos about wildlife. The question remains: Are zoos evolving toward sanctuaries of hope and redemption, or do they continue to echo with the remnants of old-world exploitation? The onus falls upon society to reassess its source of fascination with animals, urging a broader dialogue that encompasses compassion and respect for all living beings.

The evolution of zoos must align with an ethical commitment to protecting wildlife without entrapment. Engaging with animals in their natural habitats through conservation efforts, responsible tourism, and technological advancements offers a promising route. With the shift in perspective, we have the potential to create a world wherein respect for biodiversity flourishes unencumbered by the chains of captivity. Our understanding of cruelty, freedom, and coexistence will ultimately dictate the future of these institutions—a future that should be rooted in compassion, stewardship, and ethical responsibility.